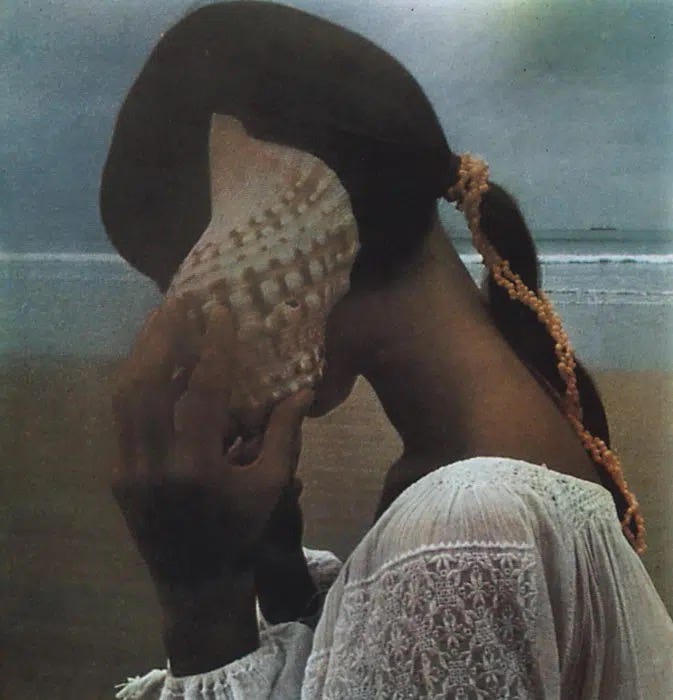

On returning to your roots

What does it mean to actively decolonize?

Hi my friends,

I realized I have been writing about decolonization without really detailing what that means to me. And to be honest, it seems to be an ever-evolving concept in my mind as I learn more about what it means to be anti-colonial and actively unlearn how I’ve been conditioned to think about the world.

If you’re new to the work of decolonization, this post is for you. I’m writing this as a way to better understand what decolonization is and what it means to actively decolonize our lives.

My first introduction to decolonization was in one of my last college classes on postcolonial literature and theory. It was taught by this tall Greek woman in her late thirties who had these thick, rectangle glasses, was extremely well-read, passionate, and had a kind of no-nonsense attitude that made you want to try your absolute best not to disappoint her.

The class was just the right amount of difficult to make it really engaging. We read incredible novels like Annie John and deeply important theory like Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. As senioritis started to kick in and I wanted nothing more than to be a part of the working world (yeah, I was a very different person back then), this class was the only thing that was keeping my love for academia and learning alive.

At the end of the semester, we had a short unit on Israel/Palestine; I was equally excited and surprised because I’m pretty sure it was the only pro-Palestine class in my college. I’m a little ashamed to admit I wasn’t very knowledgeable about the situation before then. It might have been explained to me by family, but never in enough depth for me to truly understand the severity of it. Suddenly this work connected to me in an unexpected way.

My final group project was on Black American and Palestinian solidarity for which I just grazed the surface of in my limited understanding of postcolonialism. One class was not enough to truly understand these concepts, but I am so grateful I was introduced to them because it allowed me to see 1. my privilege and 2. some of the ways colonization affects the psychology of both colonizer and colonized.

It took a long time after that to realize that I am still deeply entrenched in colonial thinking, speaking, acting—these are layers that I continue to peel back in attempt to resist being born into the U.S. —aka the belly of the beast, aka the empire, aka a patriarchal society founded on genocide, colonization, and ongoing imperialism.

Decolonization is about returning to yourself, your roots, and the earth

In Decolonizing our Minds and Actions, Waziyatawin and Michael Yellow Bird give us helpful definitions of both colonization and de-colonization:

“Colonization refers to both the formal and informal methods (behavioral, ideological, institutional, political, and economical) that maintain the subjugation and/or exploitation of Indigenous Peoples, lands, and resources.

Decolonization is the meaningful and active resistance to the forces of colonialism that perpetuate the subjugation and/or exploitation of our minds, bodies, and lands. Decolonization is engaged for the ultimate purpose of overturning the colonial structure and realizing Indigenous liberation.”

For those of us who weren’t born into a colonized or newly postcolonial state, it might be harder to spot how colonization impacts us (although I could argue, and probably will, that in the West we are in the unique position of being both colonized and colonizer).

The other day I listened to this Tedx talk about how decolonization is work that we all must do. For us non-indigenous people living in both Canada and the States, regardless of whether or not we are white, we are unwillingly born into perpetual historical bystander trauma. The speaker, Nikki Sanchez, describes this as a tactic that the settler people impose “through the invisibilization of their own role within an oppressive system.”

We have become complicit in the colonial regime as long as we do nothing about it. We are paralyzed with guilt and shame for what we feel we cannot undo.

But it is through facing the shadow of our country and people—this wretched guilt and shame—that we have any hope of decolonization.

“Your history is not your fault. But it is your responsibility.”

I think this work needs to start small. It needs to start in our own minds, in our habits, and within our families.

It is peeling back all the layers of what you’ve been told is The Way to do things. It’s realizing The Way to do things was created by the colonizer, and many rules were made arbitrarily.

It’s frequently asking yourself these questions:

Does it have to be this way?

Was it always this way?

How has it been done differently?

I am particularly interested in the idea that by connecting to where we come from, we can expose ourselves to new ways of living that could potentially revolutionize the way we interact with the world.

How much closer can we get to what we really want to do with our lives? To our ancestry, and our ceremonies, and the ways we can have reverence for the Earth?

This is what I’m starting to believe: coming back to ourselves through our ancestry and what resonates with us allows us to be guided towards a path of authentic fulfillment.

This very personal act of decolonization is one of the more enjoyable things we can do to release some of the grips capitalism and white supremacy have on us.

I’ll leave you with this passage from Decolonizing our Minds and Actions:

“The first step toward decolonization, then, is to question the legitimacy of colonization. Once we recognize the truth of this injustice, we can think about ways to resist and challenge colonial institutions and ideologies.

Thus, decolonization is not passive, but rather it requires something called praxis. Brazilian libratory educator Paulo Freire defined praxis as “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it.” This is the means by which we turn from subjugated human beings into liberated human beings. In accepting the premise of colonization and working toward decolonization, we are not relegating ourselves to a status as victim, but rather we are actively working toward our own freedom to transform our lives and the world around us. The project that begins with our minds, therefore, has revolutionary potential.”